I have lately been doing quite a bit of research around the subject of international trade for Africa. The received wisdom for developing nations is that they need to trade their ways to economic development. Not that they have many choices in the matter. The developed nations have drawn the line in the sand and everyone must conform or die. But there must be reasons why we remain underdeveloped in spite of trade. And indeed, we have struggled to trade for decades now. We joined the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1995 while China – as strategic as she is – exchanged body blows with the west and only joined in 2001, when she was sure that she could play the globalisation game. Not for China to be led by the nose as most African nations are. I have listened to three top economists who had had stints with the World Bank, United Nations and WTO in the last few days and they insist that geopolitics was a major factor in our quest for development and that many of what some people call conspiracy theories, are indeed not mere theories but the reality. We will simply not develop by the prescriptions of these international agencies. We must find our own destiny and chart our own paths.

I wasn’t one of the enthusiastic ones when Dr Mrs Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala sought and eventually landed the top job at the WTO. I wondered then why she was switching from chasing the job at the World Bank to the WTO. I knew some of the issues with the WTO and suspected that she would be frustrated by the system. Our own daughter heads the WTO but to what end for us as a people and even a continent? Is it just about the feel-good-factor? Some of the issues that remain immovable at the WTO include the inactivity of their appellate unit, the impasse around fishing (which powerful countries, despite having the ability to fish in international waters to the detriment of smaller, weaker nations are trying to write the rules to favour themselves and stymie the push from smaller nations), e-commerce (where developed countries have been enjoying unbelievable advantage since the 1980s), the tug of war between the USA and China as per Chinese social capitalism and their protection of aggressive companies making forays into developing nations, and the use of national security as excuse to protect sectors by the developing nations while China claims to still be a developing country. That we have ‘our daughter’ heading the WTO is not enough. We should be really asking what is in trade for us.

My major concern is what are we trading? I look at Nigeria’s yearly exports and it is vastly dominated by crude oil and gas (for which we get barely 30 per cent after the international oil companies have deducted most of the revenue for their technology and expertise). The rest is agricultural products in their raw form. If we record a few billions of dollars in oil and gas (which is too small for our needs), we record less than $500 million revenue per product on the other exports we push out – cocoa, sesame, shea butter/nuts, ginger, soyabean, yam, cassava and the rest. Since we obtained independence from the British in 1960, we have failed to launch.

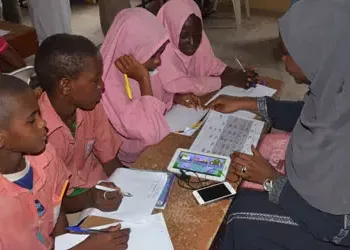

We are still a primitive, primary product economy, competing in the same world as the most sophisticated countries who are now producing 5th level goods and services. Of course, looking at the other side of the balance sheet, our largest imports – yearly – are technology and machinery. Everybody carries a phone, laptop, or tablet around these days. Some proudly carry several and Nigerians use the most expensive gadgets in the world for which they pay raw cash. Nobody else in any part of the world does that. A further examination of our import items shows that we import billions of dollars’ worth of food items, pharmaceuticals, clothing, and other basics that we should be trying to manufacture ourselves, thus totally canceling out the little we manage to get via those agric commodities I mentioned earlier.

In fact, a cursory look at the agricultural goods traded around the world – from grains, to fruits, to meat, to dairy, to oils, up to wood, shows that we only take part in less than 20 commodities out of at least 1,000 possibilities and whereas we are between the first and fifth in the listed commodities (ginger, cocoa, sesame, sorghum, etc), we are losing ground fast, and are doing absolutely nothing to even consolidate our positions. For example, none of those products are being specifically incentivised as we do say, rice. Or maybe the incentives are not just enough. We need to do a lot more. And we must challenge ourselves to extend to the off 980 other agricultural products after all we have barely utilized 30 per cent of our arable land. I am saying that we are even performing woefully in agric. So, we can as well be regarded as a lazy bunch of people. What is more? We don’t bring innovation into the agric products and so many countries around the world are producing better, cheaper alternatives. This is because our academia is detached from the reality on ground. That is why we lost ground in cocoa production to now come fifth after Cote D’Ivoire, Ghana, Cameroon, and Ecuador In fact many agric products coming from Nigeria now have to be exported through Ghana (such as cassava, yam and hibiscus flower), because our people are known to always bend the rules, by exporting mouldy products or failing phytosanitary conditions by applying the wrong chemicals to their farm products or storing in unapproved manner. We have a serious problem with regulation or lack of it. We are busy digging our own graves as a nation.

And so, I have been thinking about what we could do to try and change the situation around. Could we possibly – like they tried to do in Ghana – promote the establishment of cottage industries and aggregators of these farm products (including the agric products that we have not even tried to start optimising such as the apples and strawberries and carrots grown in and around Jos for example) such that we create industries that add value to those products, and preserve them in the areas where they usually waste and rot away? Can government incentivise such like they are intervening in many sectors presently? The challenge of course will be how to get honest entrepreneurs who can stay the course, plus the fact that since we do not produce any technology, we may have to import all the equipment needed for the processing and preservation of these products? There is also the fact that – going back to the politics of international trade which itself is a bloody contact sport – countries like ours are not encouraged to add value to products before exporting. Our processed goods are even discriminated further around the issue of standards, but it is only value-added products that can command the kind of dollar volumes that we need urgently for our survival right now. But if we add value why can we not try and sell most of what is produced here in Nigeria after all we have a large population that can drive domestic investment?

I am looking at our own cultural, industrial and productivity revolution. These ideas may have flaws here and there, but it is better than remaining a sitting duck and dumping ground and eroding our children’s future by relying on borrowing when we should be very worried about the imbalance in our productivity. If we are able to design an idea around this and start on it, we can surely stop the hemorrhage of our hard-earned dollar resources, and cause a boost in productivity and innovation. 15 per cent yearly growth rate should be achievable.