For too long, the Nigerian economy has thrived on consumption rather than production, importing what it should be manufacturing, and spending what it has not earned. The result is an economy that looks large on paper but weak in fundamentals: high inflation, low exports, and a currency constantly under pressure. If Nigeria is to secure a stable future, it must confront its most stubborn economic weakness, its chronic productivity gap.

Even among its African peers, Nigeria is not ranked among the first 10 countries in terms of productivity per capita.

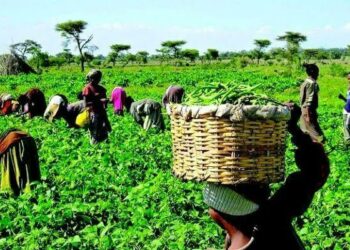

At the heart of this problem lies a paradox. Nigeria boasts vast arable land, a young and energetic population, abundant natural resources, and a huge domestic market. Yet, the nation produces too little of what it consumes and exports even less of what it produces. From food to fuel, clothing to machinery, import dependence continues to define economic life. This imbalance has widened the trade deficit, drained foreign reserves, and left the naira vulnerable to every shock in the global market.

The causes are deep-rooted. Infrastructure deficits in power, transport, and logistics continue to choke industrial growth. Manufacturers spend up to 40 percent of production costs on alternative energy, while poor roads and ports inflate logistics costs. The result: local products cannot compete with imports, and industries struggle to scale. Government policies meant to stimulate production often arrive piecemeal or are reversed midway, eroding investor confidence.

Equally damaging is the absence of productivity-driven planning. Nigeria’s economic debate often focuses on revenue, how to collect, share, or borrow more, rather than on output and efficiency. A sustainable economy cannot be built on consumption financed by debt. It must be built on innovation, skills, and value creation.

To move from consumption to production, Nigeria needs a new industrial philosophy, one that prioritises value addition, export competitiveness, and skills development. The government’s renewed focus on non-oil sectors such as agriculture, solid minerals, and digital technology is a step in the right direction, but without reliable power supply, targeted incentives, and policy stability, these sectors will not reach their potential.

Small and medium enterprises (SMEs), which account for over 80 percent of employment, must be at the centre of this transition. They need access to affordable credit, efficient taxation, and infrastructure that allows them to compete. The Central Bank and the Ministry of Industry must work in sync to ensure that interventions reach productive enterprises, not rent-seekers.

Equally crucial is education and workforce productivity. Nigeria’s labour market cannot support industrial transformation when millions of young people are leaving school without practical or technical skills. Aligning education with industry needs through vocational training, apprenticeships, and partnerships with private firms is essential.

Fiscal policy, too, must reward production. Tax incentives should go to exporters and manufacturers that create jobs and add value locally, not to importers or politically connected middlemen. Trade policy must be guided by national interest, protecting local industries where necessary, but pushing them toward competitiveness and innovation.

Ultimately, Nigeria must rediscover the discipline of production-led growth. The countries that have prospered, from South Korea to Malaysia, did not achieve it through consumption or subsidies. They invested in infrastructure, skills, and productivity. Nigeria must do the same.