Nigeria’s appetite for foreign loans is once again drawing alarm, as new data showed the federal government spent a staggering $2.01 billion on external debt servicing in just four months—between January and April 2025. That’s a jump of over 50 per cent from the $1.33 billion recorded during the same period in 2024.

Figures from the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) revealed that external debt service payments accounted for an alarming 77 per cent of the country’s total international payments in the first quarter of 2025, compared to 65 per cent a year earlier. During the period, total international payments, which include remittances and letters of credit, rose to $2.6 billion, up from $2.07 billion in 2024.

The sharp spike in debt service obligations has prompted urgent calls from economists and financial analysts for the government to put an end to what they described as “reckless borrowing,” and to channel scarce resources into infrastructure that will yield high returns on investment while curbing fiscal leakages.

A major component of the increase stems from repayments to the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The IMF has confirmed that Nigeria has completed the repayment of the $3.4 billion facility it accessed under the Rapid Financing Instrument (RFI) during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020.

“As of April 30, 2025, Nigeria has fully repaid the financial support of about $3.4 billion it requested and received in April 2020 from the International Monetary Fund,” the Fund said in a statement through its Resident Representative in Nigeria, Christian Ebeke.

March and April 2025 saw the highest spikes in debt service, with payments hitting $632.36 million and $557.79 million respectively—double the figures for those months in 2024—indicating that substantial commercial or bilateral loan obligations were cleared during the period.

Global credit rating agency Fitch Ratings has forecast that Nigeria’s external debt service will rise from $4.7 billion in 2024 to $5.2 billion in 2025. This includes $4.5 billion in amortisations and a $1.1 billion Eurobond repayment due in November. Fitch also flagged a slight delay in Nigeria’s March 2025 Eurobond coupon payment, describing it as another sign of persistent challenges in public financial management.

“Government external debt service is moderate but expected to rise to $5.2 billion in 2025… and fall to $3.5 billion in 2026,” the agency said, warning that poor revenue generation and high interest costs are serious threats to fiscal sustainability.

Even as Moody’s upgraded Nigeria’s credit rating from Caa1 to B3—citing improvements in external liquidity and progress on fiscal reforms—many economists remain wary. They argued that the country’s debt trajectory remains precarious, especially amid mounting currency pressures and sluggish revenue.

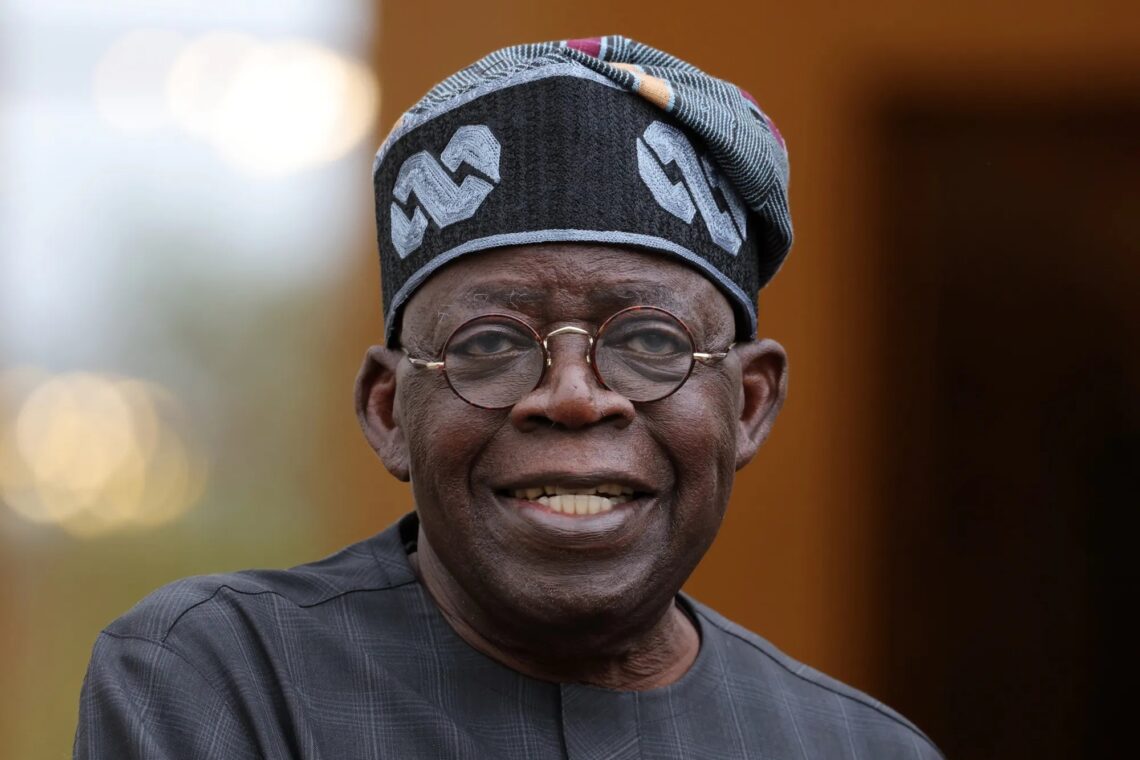

President Bola Ahmed Tinubu’s request for National Assembly approval to borrow an additional $21.5 billion to fund the Medium-Term National Development Plan has only added fuel to the fire. Analysts told NATIONAL ECONOMY the plan could expose the country to greater exchange rate risks, given that most of Nigeria’s external borrowings are denominated in U.S. dollars.

With the naira now trading at over N1,600 to the dollar, debt service obligations continue to rise in local currency terms, putting additional pressure on foreign reserves and complicating monetary policy decisions.

The African Development Bank (AfDB) projects that the naira could weaken by another six percent by 2026 due to global financial volatility. If that happens, Nigeria’s already dire debt-service-to-revenue ratio—estimated at over one hundred and fifty-six per cent in 2025—could worsen even further.

Commenting on the country’s rising debt burden, chief executive officer of the Centre for the Promotion of Private Enterprise (CPPE) Dr. Muda Yusuf, expressed serious concerns that the trajectory may no longer be sustainable. According to him, the country is plunging deeper into a debt trap at a pace that could have long-term consequences for its economic stability.

“Our debt ratios are not encouraging,” Yusuf warned. “This is certainly not the time to be borrowing so much, especially considering how high the cost of borrowing has become. The interest rates on both domestic and foreign loans are steep—even if the authorities claim most of these loans are concessional.”

He noted that external loans, in particular, pose greater risks than domestic ones. “They are harder to pay back,” Yusuf said. “By the time repayment is due, the exchange rate may have moved against us, making the naira value of repayment much higher.”

Yusuf said many state governments that borrowed externally are now “sweating” over repayment because of the spiraling exchange rate. “It’s like chasing a moving target,” he said. “As they struggle to repay, the exchange rate continues to depreciate. And because states don’t earn in dollars, they have to convert more naira to service those debts.”

He warned that Nigeria may already be drifting out of its debt sustainability threshold. “We need to reflect carefully before signing onto additional debts. The concern over debt sustainability is real,” he said.

While he acknowledged that inflows from foreign borrowing could temporarily ease currency pressures by strengthening reserves, he cautioned that repayment would pose serious challenges unless the borrowed funds are invested in high-impact infrastructure.

“If we’re investing in infrastructure—like rail or power—it can boost productivity and eventually repay itself,” Yusuf explained. “But if we’re borrowing for consumption, such as poverty alleviation or women’s empowerment programmes, then we may have a serious problem. Those don’t generate revenue.”

Echoing similar sentiments, Moses Igbrude, president of the Independent Shareholders Association of Nigeria (ISAN), said borrowing itself is not the problem—it’s what the government does with the funds that matters.

“If the government borrows to pay salaries or run day-to-day expenses, then it becomes a liability,” he said. “That’s when the currency suffers, and productivity declines. But if the money goes into worthwhile infrastructure, the project can pay for itself. It’ll enhance productivity and strengthen the naira in the long term.”

According to Igbrude, “If borrowing is for production, it adds value. If it’s for consumption, it adds no value at all.”

The numbers speak for themselves. In 2025, Nigeria’s debt service-to-revenue ratio is projected to hit

156.77 per cent.This means the country is spending far more on debt repayment than it earns, leaving less money for infrastructure, education, healthcare, and other development priorities.

Professor Tayo Bello, a development economist at Adeleke University, warned that Nigeria’s borrowing costs will only climb higher as global financial markets tighten and interest rates remain elevated in the United States and Europe.

“These pressures, combined with low foreign direct investment and persistent trade deficits, are likely to keep the naira under pressure,” Bello said.

Currency devaluation, he noted, is not a sustainable solution for a developing country like Nigeria, especially with over sixty-three percent of its population living in multi-dimensional poverty. “The last devaluation caused surging inflation, higher import costs, and deeper hardship for millions of Nigerians,” he added.

Dr. Nonye Kocha, a financial economist at Rivers State University and member of the NATIONAL ECONOMY Board of Economists, warned that another round of depreciation could be even more destabilising.

“It would raise the cost of essential imports—food, medicine, fuel—which are still subject to unstable pricing mechanisms or partial subsidies. With fragile household incomes and rising unemployment, the consequences could be severe,” Kocha said.

He called on the government to act decisively to prevent a debt and currency crisis. “This means ending non-essential borrowing and focusing only on projects with strong economic returns. We must also strengthen tax collection, plug oil revenue leakages, and broaden the tax base without hurting the poor,” he advised.

Igbrude agreed, urging the government to fast-track economic diversification. “We cannot keep depending on oil. We must expand agriculture, manufacturing, and services. That’s how to build a resilient economy and stable foreign exchange earnings,” he said.

Equally important, analysts say, is the need for consistent monetary policy and transparent economic management. Stabilising the naira, they argue, requires more than policy pronouncements—it demands credibility, discipline, and investor confidence.

The future of the naira—and Nigeria’s broader economic wellbeing—will depend on the policy choices made now.