The economic trajectory of nations is neither linear nor predetermined. It is shaped by choices, capabilities, and institutions. For too long, Nigeria’s economic development has been shackled by policy frameworks that do not create the conditions for inclusive and sustained prosperity. The country’s GDP fluctuations, rising Gini coefficient, and a development model that struggles to enhance the Human Development Index (HDI) all point to a deeper structural problem: economic growth that is neither complex nor inclusive.

Inclusive economic growth is more than an aspirational ideal. It is an imperative. The fundamental question is not whether growth is happening, but whether it is reaching the vast majority of people and creating what scholars call public value – outcomes that improve social welfare, equity, and long-term economic resilience. Public value, as conceptualized by Mark Moore, is created when governments and policymakers align resources, policies, and institutions in ways that produce tangible benefits for citizens. Unfortunately, Nigeria’s economic framework remains locked in a cycle of rent-seeking, low economic complexity, and inadequate structural transformation.

Diagnosing The Growth Constraints

Economic inclusion in Nigeria has been constrained by both macroeconomic instability and weak institutions. Nigeria’s over-reliance on oil revenue makes it highly susceptible to external shocks, limiting its ability to invest in economic diversification. The volatility of crude prices is not just a fiscal concern; it determines the fortunes of millions of Nigerians. The Lorenz Curve of income distribution in Nigeria reveals a troubling picture – economic gains are concentrated in a small fraction of the population, exacerbating inequality.

A key challenge is the failure to enhance productive capabilities. Economic complexity – the ability of a country to produce a diverse range of sophisticated products – determines long-term prosperity. Nations that successfully climbed the development ladder did so by strategically enhancing their productive knowledge, moving from simple exports to more complex industries. Nigeria’s export basket remains dominated by primary commodities with little value addition, reflecting a stagnant complexity profile.

Another structural constraint is the weak linkage between human capital development and economic opportunities. Development must go beyond GDP metrics; it must enhance freedoms, capabilities, and opportunities. Scholars have long argued that development should be understood as expanding people’s real freedoms to lead the lives they value. However, in Nigeria, education and health systems remain grossly inadequate, failing to equip citizens with the skills and well-being necessary to participate in a modern economy.

Infrastructure deficits further compound the problem. Economic growth requires a functioning logistics network, stable electricity, and efficient governance. The absence of these critical enablers raises transaction costs, disincentivizes investment, and stifles the entrepreneurial ecosystem. The challenge is not merely about resources but about governance and institutional effectiveness. Many infrastructure projects are stalled due to weak state capacity, inefficient procurement systems, and political bottlenecks.

Pathways To Inclusive Growth

For Nigeria to achieve shared prosperity, it must abandon traditional development blueprints that have failed to deliver results and embrace a more adaptive, problem-driven approach. Economic transformation requires an iterative, experimental process – one that continuously tests, adapts, and refines strategies based on real-world feedback. Development experts argue that successful economies have embraced problem-driven iterative adaptation (PDIA), allowing policies to evolve based on evidence rather than rigid preconceptions.

One critical pillar is economic diversification through industrial upgrading. Structural transformation is impossible without moving up the value chain. Countries such as Malaysia and Vietnam have transitioned from resource-dependent economies to industrial powerhouses by strategically investing in export-oriented manufacturing. Nigeria must chart a similar path, leveraging sectors where it has comparative advantages, such as agro-processing, fintech, and light manufacturing. However, this requires an enabling business environment, policy consistency, and investments in human capital to build the technical capabilities needed for industrial growth.

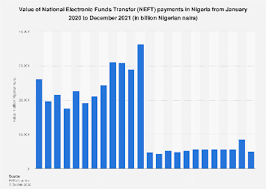

Financial inclusion and equitable access to capital must also be prioritized. The financial system remains largely exclusionary, with small businesses and rural entrepreneurs struggling to access credit. This is a fundamental market failure. Nations that have achieved broad-based growth have done so by ensuring that financial services reach underserved populations. The rise of mobile banking and digital finance in Kenya, through platforms such as M-Pesa, demonstrates how technology can bridge financial gaps, empower micro-entrepreneurs, and catalyse bottom-up economic growth.

Another vital area is governance reform. Leadership must shift from merely managing crises to building state capability. Economic growth is not just about policies on paper; it is about the institutions that implement them. A capable state is one that can execute complex projects, enforce contracts, and ensure that public investments translate into real economic benefits. Political will, bureaucratic professionalism, and accountability mechanisms must be strengthened to align state actions with long-term development goals.

Global Lessons and Local Imperatives

Nigeria does not need to reinvent the wheel; it can draw lessons from economies that have successfully navigated the transition to inclusive growth. One striking example is South Korea, which transformed from a war-torn economy into a global industrial leader by systematically enhancing its economic complexity, fostering innovation, and maintaining policy coherence over decades. Rwanda, often cited as a development success story, has demonstrated how strategic governance and targeted public investments can drive economic inclusion even in a resource-constrained environment.

At the same time, there are cautionary tales. Venezuela, despite its vast natural wealth, has descended into economic collapse due to poor governance, weak institutions, and unsustainable economic policies. South Africa’s post-apartheid economy, while making strides in social justice, continues to grapple with high unemployment and sluggish economic growth due to structural rigidities. Nigeria must take heed of these lessons and craft policies that balance economic pragmatism with social inclusion.

Leadership For Economic Change

Achieving inclusive growth is not merely a technical challenge; it is a leadership challenge. Transformational change requires leaders who understand complexity, embrace uncertainty, and prioritize learning. Leadership in this context is not about grand plans but about mobilizing actors across society to tackle real problems in an adaptive manner. Scholars argue that successful leaders operate within an “authorizing environment” where they build legitimacy for reforms and navigate political constraints while pursuing long-term development objectives.

Nigeria’s leadership must cultivate a culture of iterative learning – where policies are not static but are continuously refined through feedback loops. This means abandoning the illusion of quick fixes and embracing the difficult but necessary work of building state capacity, fostering economic complexity, and enhancing social welfare.

The future of Nigeria’s economic growth will not be determined by oil prices or external aid but by its ability to build a resilient, dynamic economy. A thriving Nigeria is possible – but only if it chooses to rethink, redesign, and reimagine its growth model with inclusivity at its core.