In the ever-evolving world of economics, policy decisions often come under scrutiny, especially when they bear significant consequences for a nation’s financial stability. Nigeria is no stranger to this, as it grapples with the aftermath of the recent policy decision to float the naira. The new Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) team now faces a formidable challenge. They must revisit the decision to float the naira and address the glaring issues that stem from it. In doing so, it is essential to recognise that the previous decision was anchored on what Nobel Prize winner in Economic Science, Daniel Kahneman, refers to as flawed judgments. Kahneman, in his seminal works “Thinking, Fast and Slow” and “Noise: Flaws in Human Judgment,” sheds light on the cognitive biases and errors that can lead to suboptimal decisions. Let us delve into this and other critical aspects of the floating naira decision.

Kahneman’s work highlights several aspects of flawed judgment that seem to have played a role in the decision to float the naira. One of the most relevant cognitive biases in this context is anchoring. Anchoring occurs when individuals rely too heavily on the first piece of information encountered (the “anchor”) when making decisions. In the case of the floating naira, the anchor might have been the idea that allowing the currency to find its own value through the market would lead to improved economic outcomes. This anchor could have obscured other viable options that could have been explored to address the economic challenges Nigeria was facing.

Another cognitive bias relevant to the floating naira decision is overconfidence. Overconfidence, as described by Kahneman, is the tendency to overestimate one’s knowledge, understanding, or ability. The previous Central Bank team might have been overconfident in their belief that floating the naira would yield positive results. Such overconfidence can lead to underestimating the potential risks and challenges that come with such a policy shift. In reality, the naira’s free float exposed Nigeria to significant external shocks and market volatility, which the country was not adequately prepared to handle.

A third cognitive bias to consider is confirmation bias. This bias involves giving more weight to information that supports one’s existing beliefs and dismissing or underweighting information that contradicts those beliefs. The decision to float the naira might have been influenced by the confirmation bias, where policymakers focused on data or reports that seemed to support the move while neglecting the potential downsides and risks associated with such a drastic shift in exchange rate policy.

Rationally, it’s crucial to question whether the naira should have been floated in the first place. The world’s currency markets are far from being predominantly on free float. Apart from the internationally convertible currencies like the US dollar, euro, and perhaps the Japanese yen, most currencies are managed or pegged in some way. The Chinese Yuan, for instance, is managed by China’s central bank to maintain stability in their currency and economy.

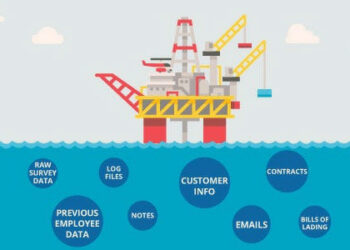

Nigeria’s decision to float the naira came at a time when the country faced a significant deficit in its trade balance and current account. Floating a currency under such circumstances can exacerbate these deficits and lead to instability. Additionally, Nigeria’s foreign exchange reserves were not at a level that could provide a sufficient buffer against external shocks. This decision raises the question of whether the former Central Bank team conducted a thorough diagnosis before prescribing such a radical shift in policy. Economist Dani Rodrik’s famous adage, “diagnosis before prescription,” underscores the importance of understanding the root causes of economic challenges before implementing policy changes. It appears that the diagnosis in this case was insufficient or based on a limited set of information.

To address the repercussions of the floating naira decision, the new Central Bank team must focus on strategic measures that restore confidence and strengthen the naira’s value. The current lack of clarity in the foreign exchange market has led to irrational behavior among market participants, which further erodes confidence. To rebuild trust in the currency market, it is essential to clear the backlog of approximately $6.8 billion of unmet commitments, including swap deals and forward deals, and commitments by airlines and other entities. This backlog not only creates uncertainty but also undermines the credibility of the Central Bank’s policies.

Additionally, it is time to end the unnecessary issuance of circulars and prohibitions on various financial products. These interventions create confusion and can disrupt market dynamics. A more stable and predictable regulatory environment is needed to encourage rational decision-making by market participants.

In closing, the words of renowned economist John Maynard Keynes offer a valuable piece of advice for the new Central Bank of Nigeria team: “The best way to destroy the capitalist system is to debauch the currency.” The responsibility of maintaining the stability and value of the naira is a heavy burden, and the decisions made by the central bank hold immense significance for Nigeria’s economic future. To navigate these turbulent waters successfully, the new team must approach the situation with a keen awareness of the cognitive biases that may have influenced past decisions and a commitment to thorough diagnosis and thoughtful prescriptions. In doing so, they can work to restore confidence in the Nigerian currency and bring about more stable and prosperous economic conditions.