Nigeria’s inflation crisis has become the defining threat to its economic stability and the welfare of its citizens. With headline inflation rising faster than wages, millions of households are being pushed into deeper poverty. Yet, amid the tightening by the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) and fiscal promises from the federal government, the underlying issue remains: the absence of a truly coordinated policy framework between fiscal and monetary authorities.

For too long, Nigeria’s economic managers have operated in silos, monetary policy fighting inflation with higher interest rates, while fiscal policy expands spending through borrowing and subsidies. This disconnect has neutralised the effectiveness of each arm of policy. The result is a cycle of high inflation, weak investment, and declining purchasing power that continues to erode public confidence in economic governance.

The CBN’s aggressive rate hikes, though necessary to curb money supply and stabilise the naira, have also raised borrowing costs for manufacturers and small businesses. Many firms now struggle to access affordable credit, forcing them to scale down production or lay off workers. At the same time, the government’s expansionary fiscal stance, through new loans, fuel subsidy arrears, and wage adjustments, continues to inject liquidity into the system, undermining the CBN’s tightening efforts.

A coordinated approach is therefore not optional; it is essential. Both arms of economic management must align around a single, credible objective, restoring macroeconomic stability while protecting growth. This requires transparent communication, shared targets, and joint planning between the CBN, the Ministry of Finance, and key fiscal agencies.

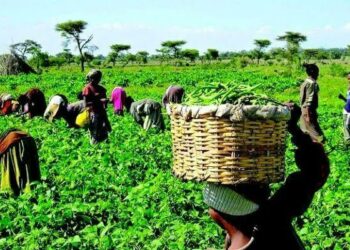

Such coordination must begin with the fundamentals. Government spending should prioritise productivity and value creation rather than consumption. Targeted investments in agriculture, power, and transport infrastructure will help ease supply-side constraints that are driving cost-push inflation. Fiscal prudence, including a realistic budget and reduced reliance on deficit financing, will also complement the CBN’s efforts to strengthen the naira and rein in price pressures.

Equally important is restoring public trust in monetary policy. The CBN must continue to operate with independence and clarity, free from political interference, while focusing on exchange rate stability and inflation targeting. Clear policy signals, rather than reactive measures, will help anchor expectations in the market.

In truth, no single institution can fix Nigeria’s inflation problem alone. What is needed is an economic “conversation” between fiscal and monetary actors, one that is grounded in realism, not rivalry. Without this coordination, Nigeria risks deepening stagflation: slow growth, high prices, and social unrest.

Inflation is not merely a statistic; it is the most regressive tax on the poor. Every naira lost to rising food and transport costs represents a shrinking hope for families already stretched thin. To reverse this trend, Nigeria’s policymakers must abandon the old habit of working at cross-purposes and embrace joint accountability for economic outcomes.

The path to stability lies not in isolated policy moves, but in a united front, one where fiscal discipline and monetary prudence march together toward a common goal: restoring confidence in the Nigerian economy.